Every June, the extended family of editors and staff from the Kenyon Review come together to recommend books they've loved (or are looking forward to reading during the summer months). For many, this season offers more time to devote to that pastime shared by so many in the Kenyon community: diving into a good book. Read on for this year's list, with recommendations sure to satisfy from every genre.

Elliott Holt, Deputy Editor

Elizabeth Bowen’s "The House in Paris" is one of my favorite novels, so when I read Tessa Hadley’s novel "The Past," I was delighted to realize that Hadley had borrowed the structure from Bowen’s book. Both The Past and Hadley’s new novel, "Free Love," are wonderfully reminiscent of Bowen’s fiction. In a 2020 piece in the LRB, Hadley praises “the thickness of [Bowen’s] detail and its colored, textured specificity.” Such a description could apply to Hadley’s writing as well. Like Bowen, Hadley astonishes on the sentence level and knows how to keep readers turning pages. Hadley claims Bowen as “one of [her] writers.” Bowen is one of my writers, too, and so is Tessa Hadley. If you haven’t yet read Bowen or Hadley, you have many novels and story collections to choose from, and summer is a perfect time to dive into their books.

Sergei Lobanov-Rostovky, Associate Editor

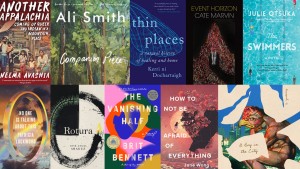

If you’ve been reading Ali Smith’s "Seasonal Quartet," her latest novel, "Companion Piece," will feel both familiar and revelatory. Smith’s narrative leaps effortlessly across time while also showing us an image of contemporary Britain as a nation of pandemic lockdowns, political despondency and Brexit banalities. The novel turns on a bit of prophetic wordplay — “Curlew or curfew: you choose” — that serves as the key to unlock its elaborately interlaced themes of climate crisis, the persistent echoes of history, and the dangers of our age’s increasingly authoritarian politics. Allegra Hyde’s "Eleutheria" also confronts the relationship between climate crisis and authoritarian politics in its narrator’s desperate search for answers to the multiplying disasters of our age. Discovering a book that promises those answers in her lover’s library, she sets off for the Bahamas in search of a utopian solution, with only the faintest awareness of the colonial history hidden behind its bright promise.

Geeta Kothari, Senior Editor

Brad Kessler’s beautifully written novel "North" traces the harrowing journey of Sahro, a young Somali refugee, as she travels from Mogadishu to New York City via Central America and Mexico, and finally to Vermont, where she crosses paths with a Catholic monk and Afghan War veteran. Kessler excels at making the reader care deeply about his characters.

Maud Newton’s "Ancestor Trouble: A Reckoning and a Reconciliation" is an engaging combination of memoir and family history as well as an investigation of our collective interest in genealogy. I was impressed by the range of Newton’s research as well as her compassion for her subjects.

In her debut collection of essays, "Another Appalachia: Coming Up Queer and Indian in a Mountain Place," Neema Avashia celebrates her childhood among a small community of Indian immigrants in West Virginia. Even when reckoning with memories of racism and bigotry, Avashia’s love for her home state and its people shines through.

Orchid Tierney, Senior Editor

I’ve read an eclectic mix of books over the last fourteen weeks, but I’ll offer a couple that deserve special recognition. First, Ye Lijun’s "My Mountain Country" (translated by Fiona Sze-Lorrain) is an evocative collection of poetry that coalesces the natural world with vibrant retrospection: “So be it, as a grain of dust / I’ve never resented my slightness.” The poet’s lyrical acuity delivers pristine observations on country environs that are stunningly embodied, situated, and local. Second, the After Oil Collective’s "Solarities: Seeking Energy Justice" (edited by Ayesha Vemuri and Darin Barney) is a short (74 pages) reflection on a future reorienting itself toward solar energy and equitable kinships. "Solarities" is a call for action for radical evaluation of not only our energy infrastructures but also our imaginations: “Solarity… demands a radical hope as well as a radical reassessment of what, of the present, we might wish to retain as we attempt to rescue our future.”

Katharine Weber, Senior Editor

Jane Campion’s superb film adaptation of Thomas Savage’s 1967 novel "The Power of the Dog" made me seek out the book. It’s extraordinary. Forty-year-old Montana rancher Phil Burbank is as vivid as he is peculiar. His strange and often nasty inner life punctuates the story, set in 1924, with some of the best close third-person writing I have ever encountered.

Ten years after "The Power of the Dog, "Savage wrote another novel, less a sequel than a parallel story, which was published as "I Heard My Sister Speak My Name," but recently reissued as "The Sheep Queen." It’s a revisiting of the same situations and characters (who were inspired by members of Savage’s family). Read them in sequence, enjoy the exquisite writing, relish the echoes, and discover this great writer of the American West.

Adam Clay, Contributing Editor

Lately I’ve been spending time with Olivia Clare Friedman’s debut novel, "Here Lies," and three poetry collections: Cate Marvin’s "Event Horizon," Ada Limón’s The Hurting Kind" and Eloisa Amezcua’s "Fighting Is Like a Wife."

All of these books manage to grapple with the gravity of the moment we’re living in now, and they provide some insight into how one might manage to keep moving forward.

Alicia Mountain, Contributing Editor

I’m excited about two debuts from Deep Vellum Publishing: "A Boy in the City" by S. Yarberry is a captivating trove of what I didn’t know I’d been hunting for in poetry — an ontological dance with chill gesticulation, highkey apostrophe, repetition that psyches me up, sex stuff, parataxis that gives and gives, the question “What am I if not a broken boy?” "Iguana Iguana" by Caylin Capra-Thomas is the book my poem-hunger’s been craving. This is my midnight snack, salty and sweet, raiding-the-fridge, licking-Flamin’ Hot Cheeto-powder-from-my-fingers book. Capra-Thomas’s imagery hits every taste bud, her humor is tasty sauce on the existential burger, her language has great mouthfeel, and the burning parts make you reach for more. I’m also turning to "Aerial Concave Without Cloud" by Sueyeun Juliette Lee for company in grief and bringing queer novel "Body Grammar" by Jules Ohman to the beach.

Elinam Agbo, KR Fellow

Grief has played a central role in nearly every book I have read this year. First, I was beautifully wrecked by Julie Otsuka’s new novel, "The Swimmers." Then I picked up Akil Kumarasamy’s forthcoming "Meet Us by the Roaring Sea." a lyrical, speculative novel set in a near future where violence is as unrelenting a reality as it is in our present moment.

Both novels traverse multiple dimensions (of space and reality) and both feature grieving daughters parsing archives of memory.

Next, I’m looking forward to Akwaeke Emezi’s "You Made a Fool of Death with Your Beauty." Because the cover is absolutely breathtaking, yes. But also because it is a story about learning to live and love again after great loss.

Kathleen Aguero, Consulting Editor

In "The Queen of Queens," poet Jennifer Martelli is a kind of sorcerer pulling out of her metaphorical hat images and observations that connect in startling ways. Pearls and female ghosts reoccur to bind the poems like the ropes of beads the speaker twists around her neck. Taking the vice presidential candidacy of Geraldine Ferraro as a starting point, these fierce poems seamlessly braid politics, culture, and personal experience. "Rotura," by José Angel Araguz, a collection brave in its honesty and vulnerability, is a lyric meditation on Mexican-American identity set in the context of social and political issues that render the speaker’s individual experience even more poignant and moving. “Four Dirges,” for example, responds to T.S. Eliot’s “The Dry Salvages” in a way that raises issues of environmental justice, class, and race. Other poems evoke the speaker’s tender relationship with his mother or show us what it’s like to be “always trying to look acceptable but feeling off.” These are books to read and re-read.

Oliver de la Paz, Consulting Editor

For poetry, dig into Jane Wong’s latest book, "How to Not Be Afraid of Everything," which is an exquisite look at family, love, food, and what it means to belong. Also, check out Kemi Alabi’s "Against Heaven" and Gary Jackson’s "Origin Story." Alabi’s book is dynamic, performative, and a wonderful debut. Jackson’s newest book is an extraordinary examination of family and the power of family narrative as the speaker looks back on recordings between himself and his Korean American mother for an understanding of the self and belonging. I also just taught a graphic narratives course and was introduced to Rhea Ewing’s "Fine: A Comic About Gender," which is a fantastic graphic narrative work that is part guidebook and part coming-of-age story, centered around the writer and artist’s own questions about their gender.

Keija Parssinen, Consulting Editor

I’ve been on a nonfiction bender lately and have found it hard to sink into novels again, but in Brit Bennett’s "The Vanishing Half," I was immediately and completely absorbed. With deft characterization through a perfectly balanced combination of dialogue, description, and action, Bennett manages to deliver a multigenerational, emotionally complex family saga with page-turning alacrity. The book centers on twins Desiree and Stella, whose origins in the small Louisiana town of Mallard, where light skin is prized among the Black residents, shape the way the twins move through the world as adults. Rebellious Desiree marries a dark-skinned man and gives birth to Jude, a child Mallard residents dismiss as beyond saving because she is “blue-black,” while Stella passes over into the white world and disappears from Louisiana and her family. The roving omniscient narration gives us glimpses into the interior lives of all of the significant characters, whose perspectives add depth and texture to the twins’ stories. But it is Bennett’s easy psychological closeness with her twin protagonists that gives the novel its emotional power — Desiree and Stella become as real as relatives, their fears and needs palpable, urgent, and heartbreaking.

Maggie Smith, Editor at Large

My favorite book so far this year — the one I’m recommending to everyone I know — is Kerri ní Dochartaigh’s memoir, "Thin Places: A Natural History of Healing and Home." It’s a love letter to place, language and nature — all things with the potential to heal, ní Dochartaigh shows us — and the prose is gorgeous.

I’ll reread it this summer, along with a stack of poetry collections I’ve bought and can’t wait to devour, including Victoria Chang’s "The Trees Witness Everything;" Hayan Charara’s "These Trees, Those Leaves, This Flower, That Fruit;" and Linda Gregerson’s "Canopy." I see a thread here.

Elizabeth Dark, Associate Director of Programs

Already a fan of Patricia Lockwood, I was primed for her first novel, "No One Is Talking About This." The first half of the book reads like the online scroll it’s critiquing, but the book’s shift midway is what has me recommending it so highly. Lockwood’s protagonist asks, “What did we have the right to expect from this life?” Readers will be grateful for joining her probe toward an answer.

It’s unclear whether Melissa Febos’s "Body Work: The Radical Power of Personal Narrative" is a craft book or a collection of essays, and I think that’s why I love it. Addressing Gass’s suggestion that to write an autobiography “is already to have made yourself a monster,” Febos counters, “refusing to write your story can make you into a monster. Or perhaps, more accurately, we are already monsters.” Both practical and personal, Febos’s book equips the writer to act on her imperative, “…don’t avoid yourself.”