The view behind Howard Sacks’ farm.

Photo Credit: Jodi Miller.

The entrance behind Howard Sacks’ farm.

Photo Credits: Bryn Savidge ‘24.

“I always get really excited when I see the first swallow back, and I text Iris and I say, ‘They’re back!’” Chrissie Laymon ’01, a Knox County native, told me with a grin on her face. Before letting Assistant Professor of Biology and Environmental Studies Iris Levin use her farmland for research, Laymon could have never anticipated the joy she would get from seeing barn swallows. Similarly, as someone who grew up in the Connecticut suburbs, I was never fully exposed to wildlife (outside of the occasional coyote) — let alone barn swallows’ importance in nature. But earlier this summer, I spent one morning capturing about 30 barn swallows with Levin and three of her student researchers.

It was a noticeably cool 62 degrees outside. Levin’s lab group journeyed forth into the rolling hills of Gambier, long tucked away from Kenyon, to set up nets in a barn. The landscape was a pastoral dream. The 10 acres of land surrounding the barn were indistinguishable from the natural area around it. Cows aimlessly roamed the pastures, the property’s creeks tempted local wildlife and a mountainous tree’s tilting branches reigned over the lime-green grass.

These 30 barn swallows are part of an active collection of over 100 swallows — from this barn alone — that Levin has been studying in Knox County since 2019. Serving as a model system for ecology, these barn swallows are a staple in modern biological research to understand different songbirds’ social behavior. Levin’s research involves capturing and recapturing barn swallows to track changes in their plumage and health over time. Once these swallows have been “banded” with a tag that has a unique color combination on their feet, Levin tracks their social interactions with other barn swallows. By observing these factors, Levin’s research attempts to understand barn swallows’ mating behavior (since swallows pick mates by their plumage) and “social network.”

As everyone ran around and clapped their hands to scare the birds into flying into the net, banded and identified them, and processed data on them, the owner of the barn was mowing the lawn. Business as usual. Though he loves chatting with Levin and always tries to persuade her student researchers to let him take a picture of them on his tractor, he was letting everyone do their thing.

But then I started wondering why he would let Levin study these birds on his property. When we read about scientific research, we usually don’t question a scientist’s methods and procedures. We also don’t always consider the intentions behind where and how a scientist conducts their experiments, even though it can have profound impacts on their findings. Maybe this is all because we subconsciously limit our understanding of scientific research to a laboratory, far removed from the rest of the world.

But what about field research? What happens when these experiments are supposed to take place in the real world? If a scientist wants to use privately-owned property, why do the owners of these sites let scientists use them? Perhaps more importantly, in a place like Kenyon that’s at once integrated in and separated from the rural areas surrounding it, what kind of relationship starts to develop between scientists like Levin and site owners like Laymon?

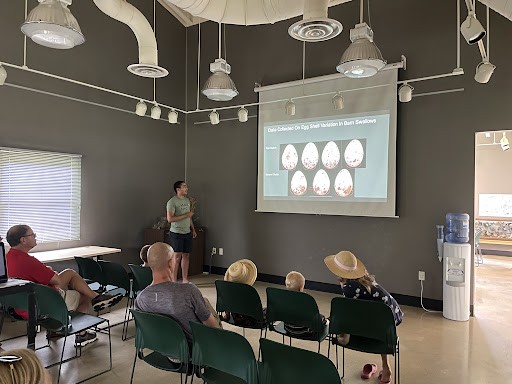

Matteus Santos ’23 presents his preliminary research results to the site owners attending Levin’s 2021 end of fieldseason party. Photo Credit: Iris Levin

On July 16, I attended Levin’s annual “end of fieldseason” party, a gathering for her students and the site owners. Everyone laughed as Levin announced superlatives like “handsomest bird” and “derpiest bird” for each of the sites. I saw all of the site owners lean in and engage as Levin’s students shared their preliminary research results. Levin happily served handmade gelato from one of the site owners. One of Levin’s students played kickball outside with one of the kids at the party. While I can’t speak for all relationships between scientists and the owners of private sites they use, I can attest that Kenyon models one of the ways it should be done. After talking to Laymon and Professor Emeritus of Sociology Howard Sacks, the owner of another site Levin uses, I understand that seeing the fruits of offering their farmland for Levin and her students to conduct research is fulfilling on a personal level — due in part to Kenyon’s Rural Life Initiative and its history.

The current Rural Life Initiative was preceded by the Rural Life Center, which Sacks founded in 1998. As someone who dedicated his academic career to researching traditional artistic and cultural practices within communities from a sociological perspective, Sacks wanted the Rural Life Center to be a space for students to interact with rural life in a meaningful way. Following in its predecessor’s footsteps, the Rural Life Initiative seeks to foster the vitality of rural life in today’s globalized society, and Levin serves as the Initiative’s inaugural Rural Life Fellow.