We’re pleased to share this holiday season’s reading recommendations from the editors and staff of the Kenyon Review. Here are some of the books that have absorbed and astonished, delighted and inspired them recently.

Elliott Holt, Deputy Editor

Hernan Diaz’s "Trust" is a critique of American capitalism, but it’s also a brilliant exploration of how we construct fiction. It’s a novel with four sections, written in four different literary styles that move from the protomodern to the modern. The book’s structure turns the reader into a detective, and putting together the narrative pieces makes one ever aware of the contract between reader and writer (and the eponymous trust required on both sides). In addition to cerebral thrills, this text contains moving stories of three strong women: Helen, Ida, and Mildred, who are all indelible characters. And there are also many moments of sly humor in this novel.

Sergei Lobanov-Rostovky, Associate Editor

Two books I’ve been lingering over lately — reading slowly to savor their beauty and process the pain they depict — are Saeed Jones’s memoir "How We Fight for Our Lives" and Maggie O’Farrell’s "The Marriage Portrait." I’m a few years late getting to Jones’s account of growing up as a Black gay boy in Texas and Memphis, but its power and poetry continue to resonate. He describes the moment that he recognized the harsh truths of his place in America after watching a high school performance of "The Laramie Project:"

"I was walking through a dusty, fluorescent-lit hallway — halfway to the assembly hall, trying with every filament of my body to look cool — when the two truths finally collided:

Being black can get you killed.

Being gay can get you killed.

Being a black gay boy is a death wish.”

His memoir is a testimony to survival against all the forms of violence — both overt and psychological — that we inflict on our children to police their minds and desires.

By contrast, O’Farrell’s novel imagines the life behind the smiling figure in Browning’s "My Last Duchess," attempting to restore the life that a jealous husband’s power, the painter’s art, and the poet’s cold irony have combined to extinguish. O’Farrell’s fifteen-year-old duchess sees her fate coming and confronts it with a combination of dread and wonder. There’s something both lovely and tragic in the way O’Farrell breathes life back into this vibrant, defiant, suffocating child.

Jackson Saul, Managing Editor

It seems difficult to discuss Anne Garréta’s "Sphinx" (translated from the French by Emma Ramadan) without mentioning the central Oulipian limitation, and perhaps it would make for its own Oulipian exercise to avoid mentioning it here. The narrator — lacking a name, any living family, and gendered pronouns — drops out of academic life to replace an overdosed DJ and meets the dancer who animates this stunning, sneakily radical novel. Alongside Garréta’s tactful depictions of desire and intimacy reside those feelings’ inversions: ennui, alienation, loss, and loneliness.

Another translated novel of queer attraction, Jenny Hval’s "Paradise Rot" (translated from the Norwegian by Marjam Idriss) has served as a coincidental companion piece to "Sphinx" in recent reading. The narrator Jo — a reserved, even repressed Norwegian biology student with little backstory — arrives in the foreign university town of Aybourne and moves into a converted brewery with the ethereal Carral. Campus novel and travel narrative turn to surreal romance as the two entwine and the similes Hval has such a knack for modulate into the literal.

Caitlin Horrocks, Senior Editor

Two nonfiction books that I’m reading and loving right now are each about writers obsessing gloriously over, respectively, an eighteenth-century Irish poem and the 1987 movie "Predator." In "A Ghost in the Throat," author Doireann Ní Ghríofa, bleary with nursing and child-rearing, devotes every scrap of time and mental energy she can scrounge to the Caoineah Airt Uí Laoghaire and its author Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill, a woman nearly lost to recorded history, whose life Ní Ghríofa contemplates in an act of devotion, resurrection, and exploration of self.

Ander Monson tells us in "Predator: A Memoir, a Movie, an Obsession" that he has seen the movie 146 times and counting. I have seen the movie zero times (so far — I’ll have to remedy this) yet the book still delights: Monson is an insightful and funny guide, exploring scene by scene how the movie speaks to larger cultural issues like masculinity or gun violence, but also how the stories we love become our traveling partners through adolescence and adulthood.

Geeta Kothari, Senior Editor

In Talia Lakshmi Kolluri’s luminous collection, "What We Fed to the Manticore," animals take center stage in stories that focus on the interconnectedness between species in a fragile and damaged world. A vulture, among the last of its kind, bears witness to the extinction of another species; a donkey provides comfort to its master when bombs destroy the zoo he’s built; a hungry polar bear and arctic fox find solace together and in ancestral mythology. These beautifully written stories cast a spell on me, and I was sorry to finish them.

Orchid Tierney, Senior Editor

It’s hard to pin down all the worthy books I have read over the semester, but the following are just a few highlights. Sylvia Legris’s "Garden Physic" turns historical plant manuals on their head by unpacking the textual pleasures of the garden ("Mad March dreams / of crane flowers, / birds of paradise"). dg okpik’s "Blood Snow" explores language, kinship, and the colonized Alaskan landscape ("Place fogged lenses on telescopic eyes. / Here brilliant colors of pollution so high"). This book would pair well with Joan Naviyuk Kane’s "Dark Traffic," which tackles climate change and the American empire in the north. Speaking of climate change, I have recently completed a book of epistolary essays: "Climate" by Julie Carr and Lisa Olstein. "Climate" weaves memory and friendship together while examining patriarchy, parenthood, loss and climate change that feels seamlessly urgent (“I need to find the power and thrust in that word: support”).

Katharine Weber, Senior Editor

I’ve been reading story collections. Fiction writers are often asked to explain what their books are “about,” which is usually a request for details of characters, plot, and setting. Reading single-author collections is the best way I know to explore what a fiction writer’s work is truly “about.” A collection of stories, whether it’s a narrative written as a deliberate sequence of stories or it’s a volume of gathered stories written over many years, reveals fascinating consistencies and variations, a genuine investigation of the fiction writer’s sensibility. Some of the gems I have recently read/re-read, in no particular order: "The Visiting Privilege" by Joy Williams, "The Complete Stories" by Truman Capote, "The Collected Stories" by Eudora Welty, "Last Stories" by William Trevor, "Lost in the City" by Edward P. Jones, "The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher" by Hilary Mantel, "The Coast of Chicago" by Stuart Dybek, "Thunderstruck and Other Stories" by Elizabeth McCracken.

Elinam Agbo, KR Fellow

I’m currently reading "American Fever" by Dur e Aziz Amna. In this sharp and refreshing take on the immigrant coming-of-age story, "it’s 2011, America is still king of the world, the cool guy’s in the White House, and . . . Americans are worried about everyone else’s safety, sated in the knowledge that their nook of the world is far safer than elsewhere, although don’t tell them why that might be." Meanwhile, a young Pakistani exchange student finds herself diagnosed with tuberculosis in rural Oregon.

I’m also making my way through Kim Fu’s haunting and transformative stories in "Lesser Known Monsters of the 21st Century." And I’ve gifted myself Ling Ma’s "Bliss Montage" for the holiday season, because it’s Ling Ma.

Cristina Correa, KR Fellow

This past year, my reading has been colored by poetic attention to the natural world and its lessons in grief and hope. Some favorites include Mayra Santos-Febres’s "Boat People" in a recent translation to English by Vanessa Perez-Rosario. This poetry collection pulls the reader into an underwater orb of anticolonial memory and resistance. In the undertow, we must relent and let the water’s will carry out until we can resurface. Here, the sea speaks inescapably the names of the dead, and acts as a holding space for their lost lives to reverberate.

Jeannette L. Clarond’s Diosas del agua translated into English by Samantha Schnee as "Goddesses of Water," which I reviewed in greater depth for the Action Books micro-review series, offers a similarly nuanced hallowed ground. In this collection, the disappeared victims of femicide speak and are honored through a paralleled thread with Coyolxauhqui, the Aztec moon goddess who was decapitated by her brother the sun god. Its liminal lyric is disquieting as it is gorgeously bound.

A one-of-a-kind companion read to these two texts, alexis pauline gumbs’s "Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals" is part-guidebook and part-love poem to marine mammal wisdom. gumbs’s acutely meditative and thoroughly researched collection of actions is a deep invitation into kinship and reciprocity. Her willingness to see marine mammals as endangered elders, teachers to whom we have infinite access if we choose to listen, is vital and healing.

A few other titles I’m eager to sink into due to some wonderful buzz around them include: Maya Marshall’s recent debut "All the Blood Involved in Love," Dionne Brand’s newest collected work "Nomenclature," and a first-time English translation of Raúl Gòmez Jattin’s "Almost Obscene" by Katherine M. Hedeen and Olivia Lott.

Kathleen Aguero, Reader

I find a particular pleasure in reading collections that chart the development of favorite poets, showcasing the breadth and depth of their work. "Paris Paintbox: New and Selected Poems" by Helena Minton shows the poet’s movement toward applying her signature precision of imagery, structure and diction in looser and more daring ways. Each poem is a delight, and the book’s journey is a poetic education. Although "Come Thunder" by Barbara Helfgott Hyett is not a new and selected, the poems are the culmination of this powerful poet’s dedication to her craft. All of Hyett’s oeuvre is striking, but the poems in "Come Thunder," many of which reprise themes from her earlier books, are astounding in their authority, their courage, their risk taking. On a different note, how equally wonderful to be introduced to a poet whose work I should have known but didn’t. Many thanks to Dzvinia Orlowsky and Ali Kinsella for "Eccentric Days of Hope and Sorrow," their award-winning translation of Ukrainian poet, Natalka Bilotserkivets. This book opened me to new ways of writing and perceiving the world.

Richie Hofmann, Reader

I’ve recently been enchanted and enthralled by Katherine Rundell’s learned but very readable introduction to the life and work of John Donne, the English poet (1572–1631) whose fascinating career careens from student and soldier to Lothario poet to major Church of England cleric. Celebrated for his difficulty, for his craggy meters, and for the violence and power of his poetic imagery, Donne’s life occurs at a period of great unrest and radical change in English history. Rundell’s spirited and often funny prose — full of passion and genuine love (devotion!) for her subject — makes a compelling story of the scant details of Donne’s early life and explicates just what makes Donne so marvelous and so weird in the history of poetry. The Donne-obsessed will be delighted by Rundell’s ardor and insight. For new readers, Rundell makes an enthusiastic case for Donne’s super-infinite poems.

Claire Oleson, Reader

Find me another poetry collection whose table of contents already reads like its own piece, and I’ll beg you for that too. Diane Seuss’s "frank: sonnets" shows us what would happen if, at the end of Kate Chopin’s "The Awakening," we got to watch Edna Pontellier walk out of the sea and stop at a gas station for a pre-packaged, post-drowning honeybun. These roaming, form-stretching sonnets walk through an American life and spend their time in Michigan, in drugs and in girlhoods where people rip at the taffeta of expected gender. This collection is its own class on form which, to borrow a phrase Seuss deploys in "[It is abominable, unquenchable by touch, closer]," shows us sonnets all "lusher than the template."

Jamie Lyn Smith, Reader

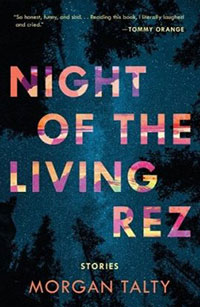

My favorite short story collection of 2022 is "Night of the Living Rez" by Morgan Talty. Set in a Penobscot community in Maine, "Night of the Living Rez" is by turns hilarious and heartbreaking. Talty is a magnificent storyteller whose work explores the ties that bind characters as family members, friends, lovers, and people.

Carter Sickels’s novel "The Prettiest Star" is the story of Brian, a young man who returns to his hometown in Appalachian Ohio so that he can spend his final days with his estranged family. Soon the word is out: Brian has AIDS. Reactions to Brian’s illness test family relationships and his hometown. Sickels’s powerfully restrained, emotionally taut telling resounds with lyric beauty, hope, and tenderness.

"Dear Miss Metropolitan" by Carolyn Ferrel is an extraordinary novel, effortlessly crystalizing a complicated story of surviving horrific trauma. Narrated in turns by dispatches from Queens journalist "Miss Metropolitan" and the three women — Fern, Gwin and Jesenia — whose years-long abusive captivity she documents, Ferrel bends time and sequence with a deft hand. The two surviving characters’ attempts to forge new lives for themselves in a demanding, imperfect world is enhanced by photos from the author’s own collection, peppered throughout the manuscript.