Monica Beletsky, the creator, writer and executive producer of the television show “Manhunt” will discuss the role of Kenyon graduate Edwin M. Stanton (Class of 1834) in the search for President Abraham Lincoln's assassin, John Wilkes Booth. She will be joined in the discussion by a panel including Wendy Singer, professor of history, Jonathan Tazewell, professor of drama and film, and Glenn McNair, professor of history.

Sponsored by the Center for the Study of American Democracy and the Bicentennial Advisory Committee.

Related Event

Watch “Manhunt” on the big screen! CSAD will screen the full series in Oden Auditorium starting at 1 p.m. on Sunday, Sept. 29. View episode screening times and synopses.

Event Actions

About Edwin M. Stanton

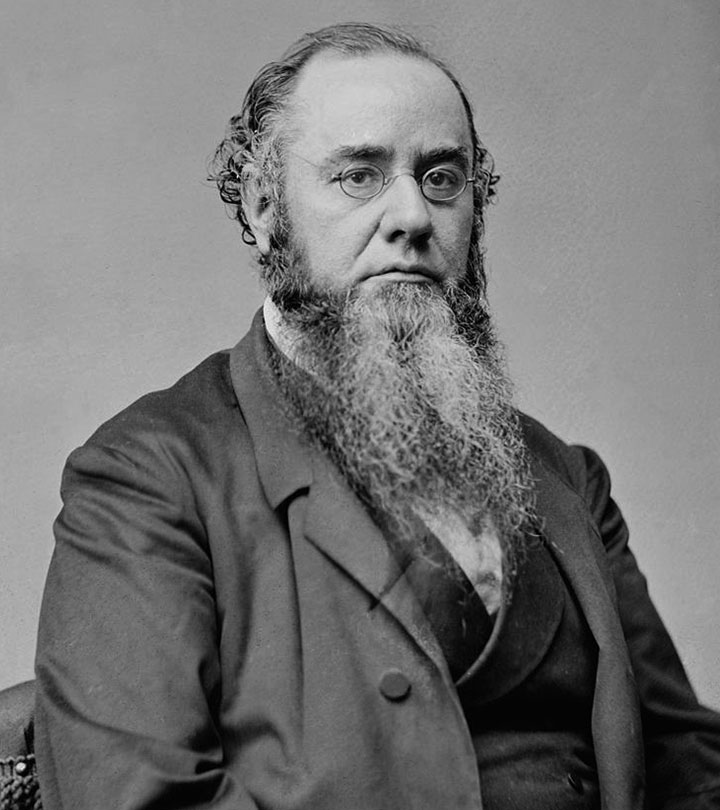

Edwin McMasters Stanton, Kenyon Class of 1834, was Secretary of War from 1862 to 1868, during the height of the Civil War and its contentious aftermath. As President Abraham Lincoln’s right-hand man (his “Mars,” as Lincoln called Stanton), he organized the war effort, marshaling the resources of the North to defeat the Confederacy. In the aftermath of Lincoln’s assassination, Stanton led the effort to track down John Wilkes Booth and the others who conspired to kill the president.

The following biography was written by Wendy Singer, the Roy T. Wortman Professor of History and special assistant to the president. You can also download the biography as a PDF.

Edwin Stanton, Kenyon and Lincoln’s Cabinet

In the final episode of “Manhunt,” the TV series about the search for Abraham Lincoln’s assassin, a flashback portrays the moment when Abraham Lincoln makes Edwin Stanton the Secretary of War.

Lincoln says, “So you've decided to be my war secretary, my Mars?”

Stanton: “I have, Mr. President.”

Lincoln: “Where would you start?”

Stanton: “By taking control of the nation’s telegraph system ... direct line to generals and the newspapers ... improve morale with positive stories.”

Lincoln: “So your big plan in telegrams?” [chuckles]

Stanton: “Yes, sir.”

Lincoln: “Can you start tomorrow, Mars?”

At the time of this encounter, the Civil War has already begun; Lincoln’s son, Willie, is gravely ill; and Stanton, unflappable and determined to win the war, sets out his plans. But Lincoln is soon assassinated, threatening the entire nation. “Manhunt” dramatically tells the story of the hunt for John Wilkes Booth and the wider conspiracy surrounding the assassination. Strikingly, the main character, the hero of the story, is Edwin Stanton, a proud son of Kenyon College, who in the “Manhunt” narrative, uncovers the plot and fights to secure Lincoln’s legacy. Like his historical counterpart, the Stanton of “Manhunt” is a lawyer and fierce loyalist of Lincoln who must navigate continued conflict with Confederate sympathizers, political rivals, and Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson.

In celebrating Kenyon’s bicentennial over the last ten months, we have taken time to acknowledge our sense of place — here in central Ohio. But equally important, is the place that Kenyon College holds in the world. Stanton, a major historical figure who helped shape 19th-century U.S. history, demonstrates Kenyon’s influence. As Abraham Lincoln’s Secretary of War, he played a critical role in prosecuting the Union war effort, and he continued to serve in U. S. government and in Republican politics in the aftermath of Lincoln’s assassination. (President Ulysses S. Grant nominated him to the Supreme Court, but he died before he could take office.) Of interesting note is that many of Stanton’s friends and associates from Kenyon joined him in public service. Indeed, as one of his biographers, William Stahr, points out, Stanton celebrated this connection, declaring: “If I am anything I owe it to Gambier College.”

Edwin McMasters Stanton was born in Steubenville, Ohio, in 1813 and lost his father at a young age. His guardian, a local lawyer named Daniel Collier, found him an apprenticeship at a prosperous bookstore — to help him support his struggling family and allow him to finish school. The bookstore owner, James Turnbull, remarked with both admiration and consternation that while Stanton had read every book in shop, it was much harder to get him to pay attention to its customers. In 1831, when Stanton was 17 years old, he asked Collier to loan him the money to attend Kenyon College. At the time it would have been a lump sum of $70 to cover tuition, room, board, fuel, and light for forty weeks — i.e., a year of education.

It is hard to imagine, though, what this place looked like in April of 1831 (just seven years after its founding) when Edwin Stanton arrived in Gambier. To describe it, we have official Kenyon records, of course, but also much of Stanton’s correspondence about the College is preserved in the Kenyon archives.

From these sources, we know that April marked the beginning of the summer term or second semester and Stanton dove right into academic life. By the start of the Fall term, he was declared a sophomore and in November, he was elected to the Philomathesian Literary and Debating Society. “Philo,” as he called it affectionately, is commemorated today by a room in Ascension Hall. Stanton was devoted to Philo, gifting the organization books he acquired and participating in several of the competitive debates. In one notable case, on the topic “Does the life of the agriculturalist conduce more happiness, than that of the lawyer?,” Stanton took the side of the agriculturalist. Somewhat ironically, given that he later took up the life of a lawyer, he won that debate. In the same year, moreover the Philomathesian society split into two factions over the ideological divide between northern and southern lines. Ultimately the southern sympathizers left, forming a new debating society, “Nu Pi Kappa.” Stanton sided with the north, staking out — perhaps for the first time — a political position of his own and one that characterized the rest of his life.

Along with Latin, mathematics and debating, life at Kenyon had other amusements. Students and faculty lived in close proximity to one another, and Stanton’s correspondence reveals a place of lively conversation about books and politics, with parties too that might end in drinking or card-playing. Stanton and his friends also talked about the women they met and courted and, in fact, gossiped about the lives of their faculty.

In 1831 Bishop Philander Chase, the founding president of the College, had just returned from a year-long fundraising tour. Registering concern about lax procedures that took place in his absence, he began to crack down on discipline and instill religious devotion. The 5 a.m. mandatory chapel returned. Meanwhile, one day — perhaps in a moment of whimsy, boredom, or resistance to rules — Stanton and one of his friends (S. A. Bronson) “borrowed” Chase’s favorite horse, “Cincinnatus,” and went for a joy ride. When Bishop Chase discovered the horse next day exhausted in the stable, he set about ferreting out the culprit for severe punishment. As the story goes, Stanton ultimately fessed up to Chase, along with a powerful defense of his character issued by a sympathetic senior theology student. In a tearful meeting with Chase, Stanton, asked for — and received — forgiveness. We do not know what immediate punishment, if any, befell Bronson — or if he were caught at all. But he survived the incident and went on to become a Kenyon faculty member, trustee and future president.

The following year, Stanton was unable to return to Kenyon. His guardian refused a heartfelt plea for continued support, preferring to direct Stanton to move to Columbus and earn a living. As it happened, his former employer, Turnbull, was opening a new branch bookshop, and offered him a position there. Of the situation, Stanton wrote to a Kenyon friend, “This I consider an absolute sacrifice of myself — soul and body — an utter destruction of all hopes and expectations, which I once cherished for it has probably not escaped your observation that I had some ‘dreams of future greatness.’”

The significance of the College to him is clear in his ongoing correspondence with Kenyon friends and the fact that even in Columbus his social circle continued to be defined by Kenyon connections — recent alumni, former employees and the church. Outside this Kenyon world, he spoke disparagingly of the men he encountered, whom he described as “impudent,” “obnoxious” and social climbers. Women in Columbus, however, he praised as a “modest, sensible, and well-informed” not to mention their “personal charms.” And indeed, he pursued a courtship with Mary Lamson (daughter of the late William Lamson, the former clerk of the College bookstore). Mary Lamson now was living in Columbus with a near relative. Referring to her, he wrote to a Kenyon friend that his renewed dedication to making a success of his new situation was inspired by “having fallen desperately in love with a young lady of Columbus.” (He married Lamson in 1836.)

Long after leaving Kenyon, Stanton maintained ties to fellow Philomathesians, including David Davis (another Lincoln aide, who later served on the Supreme Court) and Christopher Wolcott (who married Stanton’s sister and later served in the War Office). Even during his time as Secretary of War, he occasionally slipped secretly back to Gambier to see his sister and nephews (who followed their father as Kenyon students) and to visit his son, Edwin Lamson Stanton, who was valedictorian of the class of 1863.

Stanton’s remarkable career as a lawyer took him across Ohio and to Pittsburgh, California and ultimately Washington, when President Buchanan appointed him Attorney General. He is credited with shifting Buchanan’s position to oppose secession. When Lincoln was elected President, his campaign manager was, in fact, David Davis, and Lincoln brought in Stanton to serve as a legal advisor. And then on January 15, 1862, he appointed Stanton as Secretary of War. Stanton made this a very powerful position, centralizing the movement of people and goods and communications (including the telegraph) in the war office. He also convinced Lincoln to allow Black soldiers as part of the Union Army. These regiments were especially important in the battles of Petersburg and Richmond, of which Stanton asserted that the hardest fighting and greatest success came from Black troops.

Sources also suggest that Stanton was impatient with the need to collaborate with others in the cabinet and rarely took advice. But despite attacks against Stanton, Lincoln defended him. “He fights back the angry waters and prevents them from undermining and overwhelming the land ... Without him I would be destroyed.”

Indeed, the loyalty went both ways. Following Lincoln’s assassination, Stanton fought for Lincoln’s legacy. As “Manhunt” powerfully portrays, Stanton insisted — and convinced others — that the conspirators in Lincoln’s assassination be tried by a military tribunal, that their actions be seen as crimes of war. He strongly disagreed with President Andrew Johnson’s call to re-admit southern states without guarantees for the liberty of formerly enslaved people — standing up for the law anticipated by the Emancipation Proclamation and enshrined in the 14th Amendment.

By 1867 Johnson demanded Stanton’s resignation, planning to replace him with Ulysses S. Grant. The Senate, however, overturned the resignation, and Grant — already at his desk — swiftly returned the office to Stanton. In the months that followed, Stanton, though struggling with his personal health, campaigned vigorously for Republican candidates in the 1868 elections. He firmly believed that the success of Democrats (devoted as they were to the ideologies of the South) would undo the success of the Civil War. When Grant was elected President, he eventually nominated Stanton for the Supreme Court, and the Senate approved the nomination the same day. However, Stanton died in 1869 before taking office.

Stanton was a controversial man among politicians in Washington, where he made enemies for his strident manner, quick decisions, and fervent anti-southern politics. But he was a popular political figure in many quarters as well, serving as a symbol of the preservation of the Union. The United States Postal service issued a stamp with his image in 1871. (He was only the second non-President — after Benjamin Franklin — to receive that honor.) Briefly, there was also a currency that bore his image — a $1 note in 1890.

For Kenyon’s part, the College awarded Stanton an honorary degree in 1866. Unable to receive it in person, Stanton wrote that he could not be more grateful “than to receive such a token of respect and distinction from the Institution of Learning, from which the most valuable part of my education was received, and which ... has always been the object of my respect and veneration.”

As further tribute to Stanton’s career, Andrew Carnegie made two significant donations to Kenyon. Carnegie, who was assistant manager of Government Telegraph and Railways during the Civil War, developed a deep respect for Stanton and applauded his decision to consolidate those services into the War Department. In Stanton’s memory, Carnegie donated $50,000 to the College in 1904 for the Edwin M. Stanton Professorship in Economics, and a further $25,000 in 1906 to endow a scholarship fund for students with inadequate financial means. The gift was announced at "The Stanton Day" festival on April 26, 1906, when Carnegie delivered an address on "the Life of Edwin Stanton." The ceremony appears to have been quite grand, with three Bishops presiding and Stanton's grandson, Lt. Edwin M. Stanton, in attendance. In the citation for the award, Carnegie said his goal was "to enable the College to provide what may be needed for exceptional students in similar conditions [as Stanton]."

It is fitting in this moment as Kenyon celebrates its bicentennial that we both pay tribute to Edwin Stanton and this new portrayal of him in “Manhunt.” The series — like the letters we have from Stanton in the Kenyon archives — demonstrate his intensity and overwhelming dedication to his work. These characteristics followed him from Gambier to Washington and throughout his career. With the College’s own deep connections to filmmaking and storytelling, we appreciate this latest cultural representation of a man from Kenyon’s past.

Sources and Further Reading

Correspondence of Edwin Stanton (1832-1834), Andrew McClintock Collection, Kenyon College Archives.

Marvel, William, “Lincoln’s Autocrat: The Life of Edwin Stanton,” University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

Parker, Wyman, “Edwin M. Stanton at Kenyon,” Ohio History Journal. Vol. 60: No. 3, 1951, pp 233-256.

Stahr, Walter, “Stanton: Lindon’s War Secretary,” Simon and Schuster, 2018.

Thomas, Benjamin B. and Harold Hyman, “The Life and Times of Lincoln’s Secretary of War,” Knopf, 1962.

About Monica Beletsky

Emmy, WGA and PGA award nominated creator, showrunner, writer and executive producer Monica Beletsky has become known in the entertainment industry through the dynamic characters and projects she has helped bring to life. Beletsky has worked on over 130 episodes of ensemble dramas, with three series landing on various critics “Best Television” lists. Beletsky is the creator, showrunner and executive producer for the Apple TV+ limited true crime/drama series “Manhunt.”

“Manhunt,” a seven part limited true crime/drama series, portrays the investigation of one of the most widely known crimes but least understood cases; President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination. The series follows Lincoln’s war secretary and friend Edwin Stanton, played by Emmy Award-winning actor Tobias Menzies (“The Crown”), who was driven by his quest to catch assassin John Wilkes Booth and to carry out Lincoln’s legacy. The series also stars Anthony Boyle, Lovie Simone, Will Harrison, Matt Walsh, Brandon Flynn, Hamish Linklater, and Patton Oswalt. Beletsky set out to tell the investigation with a compelling range of characters from a conspiracy and true crime perspective, breathing new life into the Lincoln assassination story. “Manhunt”made its global debut on Apple TV+ in 2024.

Aside from “Manhunt,” Beletsky is well known in the industry for her roles as writer/producer on the third season of the Emmy Award nominated FX series “Fargo.” The series was met with critical praise and went on to receive multiple nominations during its third season including 16 Primetime Emmy Award nominations. As the only woman writer/producer nominated in her category at the time, Beletsky received a shared nomination for Outstanding Limited Series for a Limited Series or a Movie. She also went on to receive a Writers’ Guild Award nomination for Outstanding Long Form and PGA Award nomination for Outstanding Producer of Long-Form Television for her time on the series.

Additional notable credits for Beletsky include serving on the staff for NBC’s fan favorite series “Parenthood” for the first four seasons. She landed her first Writers’ Guild Awards nomination for Outstanding Drama Series for her work on NBC’s critically acclaimed drama series, “Friday Night Lights.” Beletsky worked at the end of season four and all of season five which went on to land multiple Emmy Award-nominations and wins.

From 2019 to 2022, Beletsky was on an overall deal at Apple TV+ where her development led to the creation of “Manhunt.” Beletsky has also developed three studio features and pilots for FX and Amazon. Additional writer/producer television credit also includes Peabody Award winning series, “The Leftovers” (S1-S2, HBO). She has worked to share her knowledge on how to write television/film with those unable to attend film school on her Twitter (@Monica Beletsky) and Vimeo by providing tips on the craft. Beletsky is an annual mentor for The Black List And Women in Film Episodic Writing Lab, which focuses on preparing women and writers of underrepresented genders for careers in writing.

Beletsky currently lives in the Los Angeles area with her two sons.