In addition to the blog posts below, writing consultants also offer tips specifically for science writing.

Douglass Day 2023

by Audrey Chen '25 and Ryan Madison '24

Douglass Day is one great way to preserve Black history for the next generation. In this era of banning books, limiting what we can access and deliberately misunderstanding CRT, Douglass Day offers hope and an outlet for celebrating Black history.

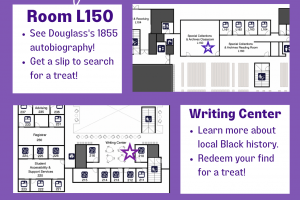

We write today to announce that Kenyon’s very own Writing Center on the second floor of the library will be collaborating with the Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, Chalmers Library, and other community partners to host a Douglass Day Celebration on February 14th, 2023 from 12 noon to 3pm! The event will mark Douglass’s 205th birthday and there will be a collection of activities available in the Writing Center as well as in rooms L150 and 330 (see this map for more details). Douglass Day is a very special occasion that takes place as part of Black History Month, some argue it was the impetus to start Black History Month, to celebrate Frederick Douglass’s chosen birthday, February 14, 1818. All students, staff and faculty are encouraged to attend.

Featuring a transcribe-a-thon, this event will bring you the exciting opportunity to transcribe the works of a famous writer and activist, Mary Ann Shadd Cary. Transcription is the process by which we take handwritten and typewritten documents and put them into electronic forms to preserve the materials for current and future generations to explore. Cary’s work is particularly important because she was the first Black female publisher and newspaper editor in North America. In 1848, she penned a letter to Douglass’s anti-slavery newspaper, the Northern Star. Later, they together published articles that advocated racially-integrated education. While you transcribe, we’ll be playing recordings of Frederick Douglass’s speeches read by Black actors.

In addition to the transcription event in room 330, you will be able to see Douglass’s autobiography from 1855 in room L150, and learn about his visit to Mount Vernon in the Writing Center. A raffle will also be taking place at the event while snacks from a local bakery will be provided for you to enjoy! Big thanks to Chalmers Library, ODEI and other campus and community partners for supporting this event. Please join us in sharing our community’s connection to Frederick Douglass on this special day!

For more information about this global event, check out douglassday.org.

Semicolon

By Molly Fording '23

When used correctly, a well-placed semicolon can help control the flow of your writing. It can add a needed change to your typical punctuation style, and lend an air of sophistication to your paper, email, blog post, or any other piece of writing. When used incorrectly, the effect is… well, not as great. So, here’s how to use semicolons correctly!

What is a Semicolon?

A semicolon is a punctuation mark that can link two or more independent clauses that are closely related. It can link independent clauses that are connected by conjunctive adverbs or transitional phrases. Also, it can be used to separate items in a list. Like a period or a comma, it signals a brief pause that helps to control the flow of a text. However, the semicolon is not interchangeable with a period or a comma; it implies a longer pause than a comma, but is not as strong as a period.

How to Use a Semicolon?

The most common use for a semicolon is to connect two independent clauses. The words before the semicolon should form a complete sentence, and after the semicolon should form another complete sentence which is closely and logically related to the first sentence.

Example: “Maria was tired of working in the bakery; she was on her feet all day and always got home late.”

A semicolon can also be used when you have two independent clauses joined together with a conjunctive adverb or a transitional phrase. A conjunctive adverb is a word that brings together two complete sentences. These are words like furthermore, likewise, however, still, meanwhile, etc. A transitional phrase is very similar to a conjunctive adverb, as these phrases are used to smoothly transition from one idea to the next. Examples include as well as, in other words, as a result, in conclusion, and on the contrary.

Examples: “The detective was suspicious; however, this lead looked promising.”

“The teacher made a mistake in her grading; as a result, she received many emails from upset students.”

Finally, you can use a semicolon to separate items in a list, if any of the items are long or contain internal punctuation, like commas. This helps a reader understand what the list items actually are without getting confused by any other information in the list.

Example: “She had packed quite a lot for the picnic: three baguettes, fresh from the bakery; several types of jam, so everyone could choose their favorite; a pitcher of ice-cold lemonade, which she hoped would last them most of the day; and an enormous bowl of cherries.”

Common Mistakes:

Here are a few examples of how NOT to use a semicolon.

• Don’t capitalize the first word after a semicolon — it’s not the same as a period! Only capitalize the word following a semicolon if it is a proper noun or an acronym.

• Don’t use a semicolon to connect non-independent clauses; for that, you need a comma.

Incorrect: “Because he loved animals; he agreed to watch his friend’s cat.”

Correct: “Because he loved animals, he agreed to watch his friend’s cat.”

• Don’t use a semicolon with a conjunction. A conjunction is a word that links independent clauses (and, or, but). If you’re using a semicolon, you don’t need to use a conjunction.

Incorrect: “She was so happy to have gotten the job; and she started packing immediately for her move across the country.”

Correct: “She was so happy to have gotten the job; she started packing immediately for her move across the country.”

I hope this article was helpful! Go forth and use semicolons to improve your writing and dazzle your professors.

Citations:

The Value of Freewriting

By Davida Harris '22

What is freewriting and what are the benefits? Learn how to free-write, and hopefully, these tips will help you during your writing journey.

What is freewriting?

One way to brainstorm.

A strategy to write for a fixed amount of time without stopping.

A great way to start prepping for a paper!

How do you free-write?

1. Examine your prompt or essay idea.

2. Choose a time to free-write for (15-20 minutes is ideal)

3. Start writing and don’t stop! It doesn’t matter what you write as long as you keep your hands moving.

What are the benefits of freewriting?

Staring at a blank screen is intimidating. So, freewriting stimulates your brain and eases you into writing your assignment or piece. It sparks chains of thoughts, that can help inspire you and start to organize your argument.

It lets all of your ideas flow out of your head, without second thinking.

It stops you from censoring “bad” ideas. All ideas are good in the brainstorming phase!

When freewriting...

Do:

• Keep writing for the entire time period.

• Write in sentence and paragraph form.

Don’t:

• Worry about grammar/punctuation.

• Censor your ideas even if they seem bad or crazy.

Happy freewriting!

Evidence

By Paige Bullock '21

Learn how to provide and interpret evidence, justify your interpretation and make your final claim.

Say that my evidence is the picture above, and my claim is that this bear is angry.

My reader may have some questions: "I only see a mouse — what bear is this person talking about?" "This bear looks friendly — why does this person think it is angry?" "Why do we care if the bear is angry, anyway?"

If I were clear or precise enough, my reader wouldn't question me. So I follow this process, in order to avoid their questions:

• Give relevant evidence: Here is the bear I am talking about: (picture of bear)

• Interpret evidence: The artist depicted a bear here, reaching forward with one paw to aggressively swipe at the viewer.

• Justify this interpretation: While this creature may appear mouse-like because it's covered in fur and has large ears with small eyes, we can tell that this is a bear because of the nose: bears have sizable noses with visible nostrils, while mice don't. Furthermore, we can tell that the bear is trying to swipe at the viewer, rather than wave hello, because its claws are out. The bear wouldn't expose its claws if not for a violent act.

• Make your claim: Based on this evidence, the bear must be angry — if the bear were not angry, the bear would not have a motivation to violently strike the viewer.

• Connect to your thesis: By depicting the bear as angry and threatening, the artist is trying to demonstrate that bears are the worst animals.

Hopefully, this explanation would eliminate any questions my reader may have. Note that I don't necessarily agree with this argument/thesis! My personal opinion is that bears are great, and this is a friendly waving bear. However, it doesn't matter if this interpretation/claim is correct, just that it's a strong, well-explained argument.

Paige is the writing liaison for Professor Lisa Leibowitz's "Quest for Justice" class.

Equity in Writing

By Bennet Andrassy

Learn how to articulate your argument in a respectful way to other beliefs and ideologies.

Doing Your Research:

For Persuasive/Argumentative pieces, be sure to examine as many perspectives on the topic as

possible. Though some of these perspectives will surely contradict your own, understanding

oppositional viewpoints will give your writing depth, and allow it to relate to a larger audience.

Commit to educating yourself on the historical context of the terminology you use. Many words

are attached to historical connotations, some of which are now deemed offensive or unsuitable for academic writing. Terms describing race, gender/sexuality, and socioeconomic class are

especially important to research before using.

For citations (especially primary sources), research the historical and cultural background of the

writer before including their words in your piece. If you discover clear biases in the source

material you are citing, it is your responsibility to make those biases known to the reader.

Awareness of Content Biases:

· Consider whether your own socio-cultural background influences the content of your writing. If you are writing about marginalized groups from an outsider’s perspective, for example, you may want to acknowledge your own social status relative to the topic you are analyzing. This will make your piece more honest as a whole, as well as prevent it from coming off as condescending or pedantic.

· Ensure that any sources you cite are of a legitimate academic origin, and do not push an agenda of inequity. If you’re concerned about the ethics of a source you’d like to use, including a note about the biases of your material is a good mechanism for keeping your writing objective.

Respectful Tone & Diction:

· Think about your intended audience, and try to foster a tone that will communicate effectively to them. If an author writes with a tone that treats the reader as “less than”, it will lower the accessibility and enjoyability of your piece.

· Avoid derogatory or condescending words and phrases, to the best of your ability. Consider whether you are using exclusionary language that might alienate certain readers, depending on their background.

· Be careful not to “otherize” demographic groups. Otherization occurs when one writes about a group that is foreign to the author, and consequently presents the group as strange or aberrant.

· When describing people, try to define them on the basis of their relevance to your piece, rather than on their race, creed, gender, sexuality, etc. It may be necessary to mention the demographics of a person for the sake of your paper. However, when doing so, avoid using it as a sole descriptor; this reduces people to their societal labels.

A Guide to Citation Resources

By Sonya Marx

An aide to help navigate the world of citations and some resources you could use to better your understanding of each one.

Some of the most common questions college writers have when working on an assignment have to do with citations. When do you use them? How do you use them? What to do when you don’t know? Do you use parentheses? What is the difference between a footnote and an endnote? What about capitalization and punctuation? Can you go to prison for accidental plagiarizing? This concise guide is here to help you understand how to respectfully acknowledge your sources and avoid plagiarism through proper citations in three of the most commonly used styles: MLA, APA, and CMS.

Citations FAQ

When do I need to cite my sources? The short answer is that you need to use citations whenever you are using information that is not your own. This includes directly quoting a source, paraphrasing someone else’s words, and employing factual information which you obtained from a source. If the statement you’re making was informed by something that didn’t come from your brain, you need to cite it. If you’re still unsure whether or not you need to cite, this handy list should help.

Which style should I use? Most often, your professor will let you know which citation style is appropriate for a given assignment or a specific academic discipline. In general, History courses tend to use CMA, English courses tend to use MLA, and Psychology courses tend to use APA. However, sometimes a professor will assign a different style depending on the assignment, and in some areas, like Anthropology, academic journals don’t always rely on a single citation style, so it can be more difficult to know for sure which one is appropriate. If your professor doesn’t specify the style they’d like you to use, just ask!

MLA Resources

Many students may already be familiar with the Purdue OWL. This is a great place to understand formatting more generally, as well as citation specifics for everything from books to online resources. They also have sample citations, and this helpful video tells you everything you need to know about in-text citations. Even for seasoned writers, this site is a great resource to have bookmarked for easy access to clear and credible citation advice. The OWL also has guides for CMA and APA styles.

CMA Resources

If it’s your first time taking a college-level History course, you might not be familiar with Chicago Manual Style. In that case, the Chicago Manual of Style website will be your best friend. This quick guide tells you everything you need to know about the two systems, including notes and bibliography and author-date. They even have a page specifically designed for students, with quick links to common questions about citing and formatting, as well as more general writing advice about working through writer’s block, choosing a research question, and writing a strong introduction and conclusion.

APA Resources

In addition to the OWL guide mentioned above, the American Psychological Association also has its own website, which offers a wealth of information, including how to correctly format a title page, best practices for referencing sources, and a comprehensive guide to in-text citations. Depending on the assignment, some professors won’t require a formal reference list or a title page, so it’s important to check your assignment sheet or get in touch with the professor to avoid doing unnecessary work.

Kenyon LBIS Website

Finally, if you still have questions about citing your sources correctly, Kenyon’s own LBIS is a great resource to get all of your questions answered. You can access citation manuals directly here, make an appointment to chat one on one with a librarian, or get in touch with the Research and Reference Desk for more assistance.